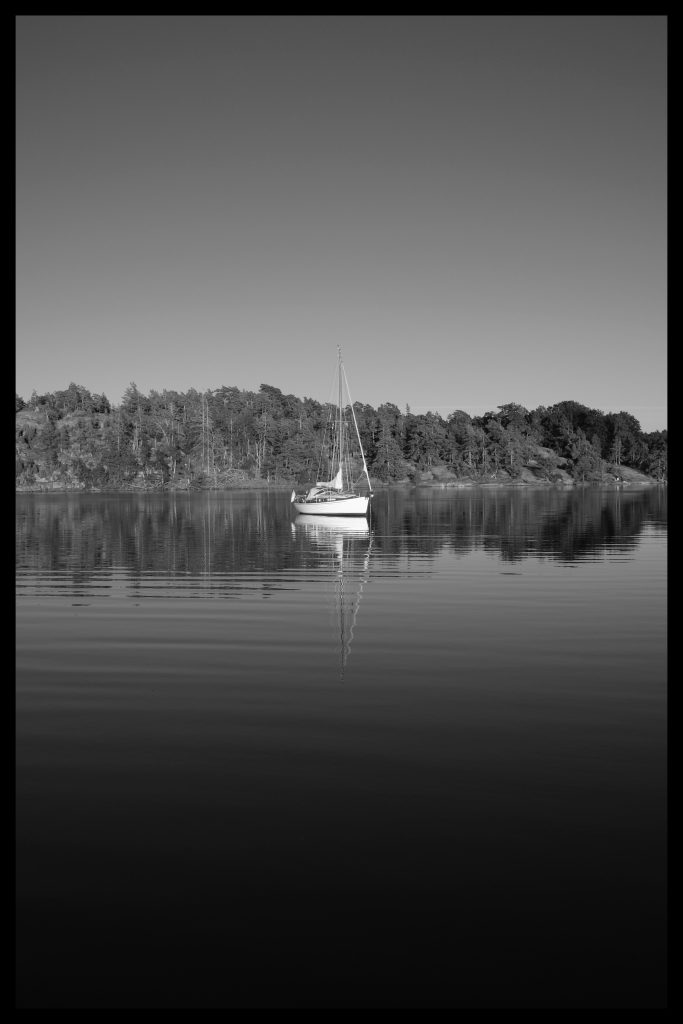

With Hugh and Liz on board we headed off from Nyköping to Ringson – 15.3 miles. We sailed, under jib only the whole way, weaving through the islands finally coming out to the meteor crater beside Stendörren nature reserve and from there into Ringson. Once there we anchored and headed ashore by dinghy. From there on, Hugh takes up the story ……

The scene was perfectly set: Having gone ashore at Ringson, a granite island in the Swedish archipelago, we tramped through the sparse woodland looking for the path that Andy said would lead us to a collection of old timber buildings marked on the map as a riding school.

A group of sailors making a shore landing on an a remote Scandinavian island – an innocent holiday jaunt ? Or the opening scene in a Scandi-noir drama with a missing person and a detective in knitwear that is literally to-die-for?

We took reference points – the fallen tree, the buttercup meadow, the stony outcrop – that we thought would, in due course, guide us safely back to the dinghy, which was now on land and lazily tied to a tree stump.

We tried several of the numerous deer trails that ran here and there through the woods and across the buttercup meadow, but each became slowly less distinct and more tangled and overgrown, or blocked by branches, or terminated abruptly by an impassable rock or ended vaguely at the edge of an unmarked patch of grass. The island seemed as deserted as the clear skies above.

We soon mentioned to each other that we’d passed several similar fallen trees and beyond each stretch of woodland was yet another buttercup meadow. The landscape had numerous rocky outcrops. The island, we now realised was a maze, with numerous forked paths and identical features, as if designed deliberately to confuse visitors. The journey back to the dinghy was clearly going to be guesswork. The skipper was getting nervous so we turned back, roughly certain of our course, but now on different trails, walking faster, by turns sure and then unsure of our route.

Midsommer was to be celebrated in Sweden in a couple of days with maypole dancing and other rituals. The beginning of astronomical Summer and the absolute end of the long dark Swedish winter. These few days before midsummer, when darkness has just hours left to make its sorry mark on the year.

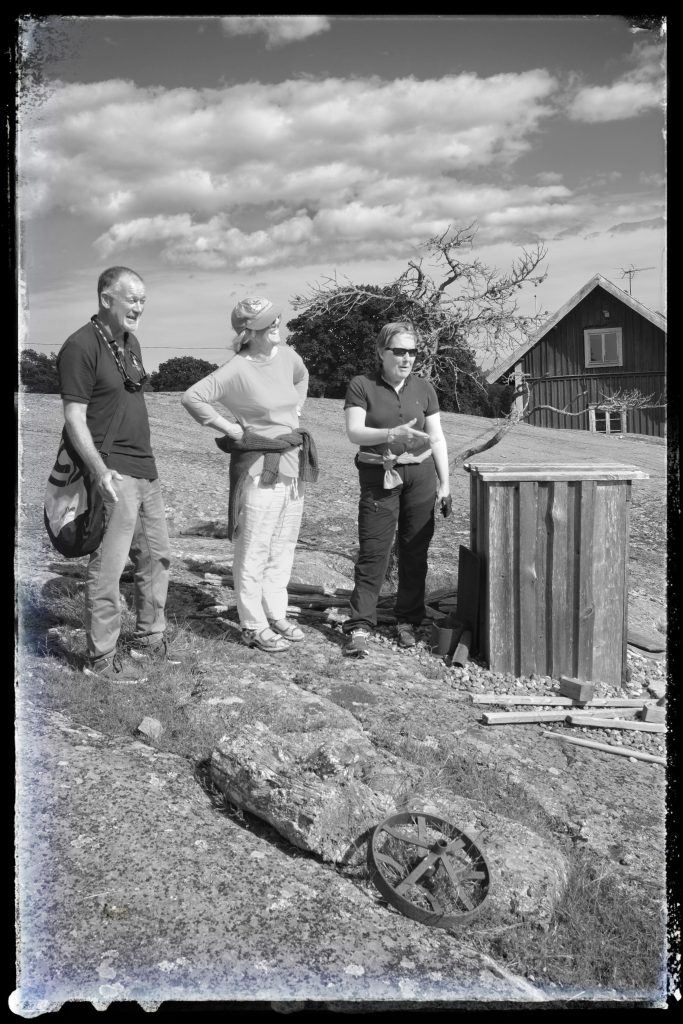

By luck more than judgement, we came across a vehicle track that led in one direction to a jetty and in the other towards the centre of the island and, we assumed, the riding school. Sure enough, after a short walk a picturesque complex of wooden buildings came into view.

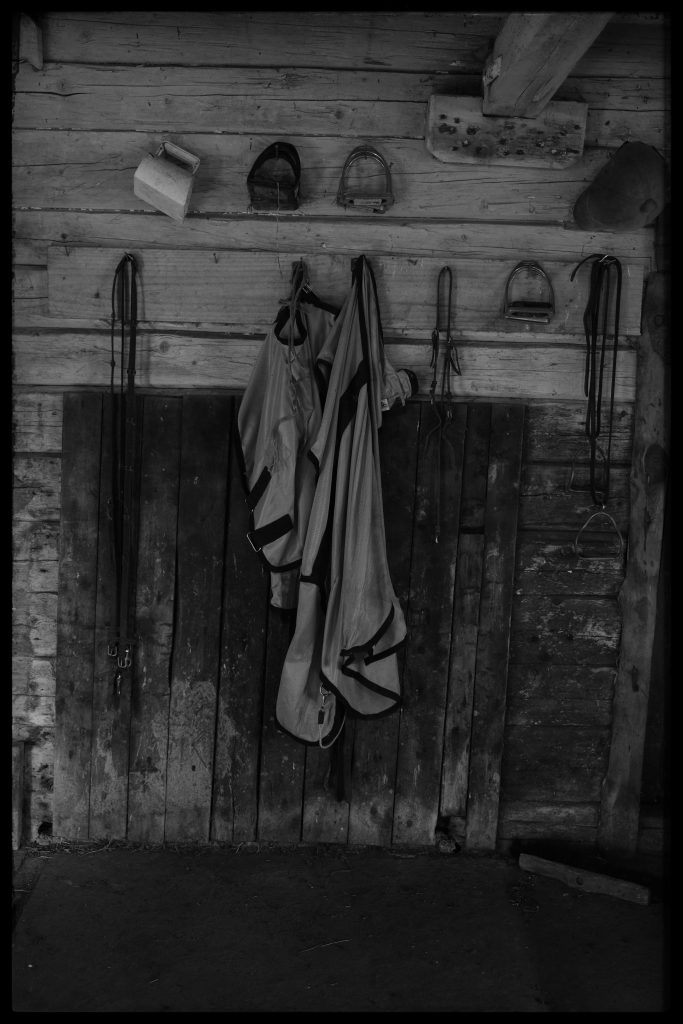

The doors to the nearest and largest building were unlocked and hanging open, as if someone had left in a hurry. With a nervous ‘hallo’ we walked inside. All around in the gloom and stillness, was evidence of equestrian activity: saddles and other riding tack were carefully stored on metal hooks or placed over the wooden divisions between stalls, riding garments were hanging lifeless from pegs, the floor was swept immaculately. Thin lances of sunlight shone down from gaps in the eaves, motes of dust were suspended lifeless in their beams. The scene felt like a stage, awaiting the arrival of a protagonist.

Beyond the stables were several residential buildings, every one deserted. Cupping hands around our eyes and looking through the windows we could see vacant dining tables where once a family gathered for meals, armchairs where once a father sat and read a book, or a grandmother dandled a child on her knee. In the wooden houses and in the stables was the weight of absence – the absence of any human being, as if the traces of former occupants had been wiped away and surfaces had been polished clean by a meticulous hand.

I wanted to stay and take photographs. Andy, Anne and Liz decided to head back to find the dinghy and the the safety of yacht Charmary. ‘It’s five now. We’ll meet you at the jetty at seven.’

Around the buildings was extensive evidence of animal remains: deer and elk antlers hung from a garden lattice where you would expect jasmine or a clematis to be climbing. On a small shelf that might otherwise have supported an ornament or decorative plaque, sat the skull of a small animal next to a bundle of rusty nails. Behind the stables, in a field of long grass and daises, the skull and antlers of an elk was positioned on the driver’s seat of a rusting hulk of farm.

Crouching to take a picture of the elk’s skull, and staring as I had to into the dead creature’s empty eye sockets, I had a growing sense of someone else present. The skull had the visage of a pagan divinity who I had perhaps disturbed. It was nothing more than an innocent breeze and then a hum reverberating in the summer air. I walked around to the stable to see a quad bike approaching, and then the appearance of a man dressed in olive green fatigues and industrial ear defenders. He looked as taken aback as me.

They used say that the way to stay safe on the New York subway is to look like the kind of person who might be concealing an axe under your coat. In this spirit I approached the quad bike with purposeful strides and a confident greeting.

‘English?’ He asked.

I nodded. ‘London.’

‘Can you explain something?’ His voice now had an edge of irritation.

‘I was just taking photographs,’ I said apologetically, holding up my camera.

‘I can see you are taking pictures.’ He leant forward. ‘Can you explain why the UK voted for Brexit? And Boris Johnson.’

The image of the elk skull flashed up in my mind, and its unfathomable sockets.

‘I can’t explain it,’ I said, ‘it’s insanity.’

He nodded. ‘My name is Nils’. He extended a hand which I gripped warmly.

‘I’m Hugh.’

‘This is my island, I grew up here. There are elk here and deer and beavers. You are very welcome. You should spend more time exploring.’

‘Sadly I’ve got to go back to my Island,’ I said, ‘the UK.’

‘And Boris Johnson,’ he added.

Again the sockets of the elk skull were looking back at me, and I made my way back to the jetty and to Charmary.